| Free articles and cheat sheets from Digital Camera World: How to shoot fast-moving objects (see the graphic at the bottom portion of this post) How to take control of your shutter speed for cool effects Slow shutter speed vs. fast: how to maintain a consistent exposure 3 camera lessons every new photographer should learn Best shutter speeds for every situation Free action photography cheat sheet |

The shutter is a device used to control the time that light is allowed to act on the film. Besides controlling the duration of the exposure, the shutter more importantly, controls the exact moment the film is exposed to the light.

Like the ISO (International Standards Organization) numbers and the f/numbers (please review the Wikipedia article on photographic lenses), the shutter speeds are a universally adopted series of numbers. The ISO numbers are an index of the film’s sensitivity to light, while the f/numbers, on the other hand, are a measurement of how small or how big the lens opening is.

The shutter speed is the time the shutter remains open, allowing light to hit the film. Measured in fractions of a second, each change in shutter speed setting is considered as one stop (just like apertures or lens openings). The time during which the shutter remains open is controlled either mechanically or electronically.

Notice that on your camera’s shutter speed dial, the numbers do not appear as fractions; only the denominators appear, thus 1/1000 would appear as 1000, 1/125 as 125 and so on. Full seconds (numbers appearing after 1/2 sec) are often indicated by a different color. Remember that shutter speeds are fractions of a second; 1/2000 really means that you take one second and divide it into two thousand parts and then take only one part of that 2,000 parts.

Shutter speed, freezing movement, and light conditions

(1) When you want to freeze the action, as in a shot of a basketball player dunking the ball, a high jump athlete doing the Fosberry Flop, etc, use a fast shutter speed like 1/250 sec. or higher.

(2) When you’re shooting your subject under bright lighting conditions, use a fast shutter speed. A slow shutter speed will allow too much light to reach the film and will consequently overexpose your shot.

(3) When there isn’t much light, as when you’re shooting early morning or late afternoon, or you’re inside a room - use a slow shutter speed like 1/60 sec. or slower. A high shutter speed will restrict the amount of light striking the film and will consequently underexpose your shot.

Remember, however, that you have to consider the aperture or lens opening for the correct exposure.

Freezing movement

When you want to freeze movement, there are factors other than shutter speed that you have to consider: (1) subject distance; (2) focal length of the lens; and (3) direction of the movement.

When using wide angle lenses to shoot subjects which may be far off from you, or moving away from you, you can use slow shutter speeds to freeze the subject. When you are using telephotos, you have to use fast shutter speeds to freeze movement of subjects which are, in Karen Carpenter’s song, close to you.

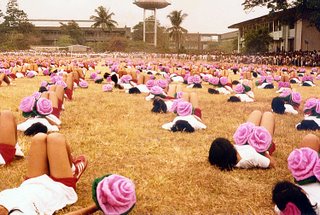

If the subject is moving away from or towards the camera (like the boys in the picture above rushing to the venue of the Math Quiz competition), you can use 1/60 sec. or slower since the camera senses little movement in this kind of situation. In sporting events like racing (sports cars, cycling, track and field, etc), position yourself at the corners of the track. Thus way, your subject will be turning towards you and you will be able to use even slow shutter speeds.

If the subject is moving away from or towards the camera (like the boys in the picture above rushing to the venue of the Math Quiz competition), you can use 1/60 sec. or slower since the camera senses little movement in this kind of situation. In sporting events like racing (sports cars, cycling, track and field, etc), position yourself at the corners of the track. Thus way, your subject will be turning towards you and you will be able to use even slow shutter speeds.

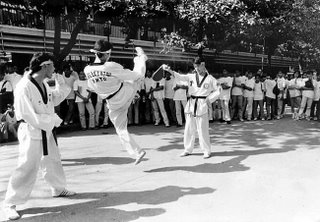

If the subject is moving in an oblique way with reference to the camera, like this Tae Kwon Do black belter in the picture above, use l/125 sec or higher.

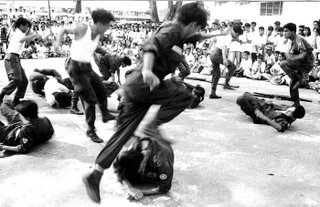

If the subject is moving across the film plane, you have to use 1/250 sec or higher. Otherwise, the subject will come out blurred like the boys in the picture above where I used 1/60 sec.

Blur as a means of expressing movement

I could have frozen these guys (in the picture above) in mid-air by using a much higher shutter speed, but sometimes, blur is can express movement better. Speaking of blur, you can create it by either using a slow shutter speed, or by deliberately shaking or jiggling your camera while taking your shots. The end result is, of course, difficult to predict. You could probably mess up a lot of your pictures, but you may also come up with some pretty neat, abstract designs. (By the way, photographer Ernst Haas became famous for his deliberately-blurred pictures.)

Flash synchronization speed or the x-synch

On your shutter speed dial, you’ll find the number 60, 90, 125 or 250 (remember that these are really 1/60, 1/90, 1/125 or 1/250th of a second) either marked by a lightning bolt beside it or set in a different color than the other shutter speeds. This number or speed is your camera’s “flash synchronization speed” or simply the “x-synch”.

The x-synch or the flash speed, simply put, is the highest shutter speed you can set on your dial when using your flash. So, if your x-synch is 1/60 sec, do not set your shutter speed dial to a higher number, for example, 1/125 or 1/500 sec. If you do, your pictures will come out with one half of the frame totally black, devoid of any image.

So you can’t use a speed higher than your x-synch. The question is, can you use a speed slower than the x-synch? The answer is yes (if you want more illumination for your subject, that is).

B-setting

Besides numbers, you’ll also find the letter “B” on your camera’s shutter speed dial. The “B” stands for “bulb” and is used when you need exposure times longer than the slowest speed available on your camera. Thus, if your slowest speed is 8 seconds, and you need an exposure time of say, 45 seconds (as when you’re doing night photography), you need to use the B-setting.

Photography’s high sounding-terms

Reciprocity failure, hyperfocal distance, flash synchronization speed, x-synch, B-setting ... photography really has a lot of high sounding terms. Don’t be intimidated however by these terms; there are veteran photographers who may not have heard of these terms and yet, they can create a lot of good pictures.

The point is, don’t go about thinking that you’ll become a better photographer by simply memorizing the definitions. You become better by learning the basics, which includes knowing, not memorizing, what these terms mean and applying them when you go out to shoot. Photography is definitely a hands-on activity! As the late martial arts superstar Bruce Lee once said, no one learns how to swim on dry land. I believe him. I tried! I nearly drowned!