What is depth of field?

Simply put, “depth of field” is the distance between the nearest and farthest point from the camera that appears in focus (meaning sharp and clear). In practical terms, the depth of field extends, in terms of area, about 1/3 in front of the subject and about 2/3 behind the subject. Any object or portions of the subject below this 1/3 area and beyond this 2/3 area will appear blurred or out of focus.

Wide depth of field

A “wide depth of field” means that everything is sharp and in focus from the foreground up to the background. You need a wide depth of field in the following situations:

(1) to convey the mood and atmosphere of your subject;

(2) for landscapes, sceneries, and interiors;

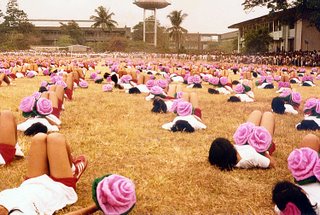

(3) for group shots;

(4) when focusing is difficult; and

(5) to give maximum visual information about your subject by bringing out the details.

Some examples of pictures with a wide depth of field

Shallow depth of field

On the other hand, a “shallow depth of field” means that the area of sharpness or clarity is very limited, and the background (or the near foreground) is blurred or out of focus. You need a shallow depth of field in the following situations:

(1) for portraits, so that your subject will “pop out” of the background;

(2) to hide a cluttered background;

(3) to avoid distractions or obstructions in the background or foreground;

(4) to convey depth; and

(5) to isolate certain details of the subject.

Examples of pictures with a shallow depth of field

Again, for the purposes of the topics we will discuss below, please review the Wikipedia article on photographic lenses.

The bigger the number, the smaller the lens opening; the smaller the number, the bigger the lens opening

The SLR (single lens reflex) camera has an “iris diaphragm” which consists of crescent-shaped blades that make a circular opening in the middle of the lens and which controls the size of the aperture or the lens opening. The aperture setting ring (or simply aperture ring) in the lens controls the size of the hole made by the iris diaphragm. For example, setting the aperture ring at f/11 will reduce the size of the hole while setting it at f/4 will consequently enlarge the hole. The rule is, the bigger the number, the smaller the lens opening; the smaller the number, the bigger the lens opening.

Fully automatic diaphragm

SLR cameras have what is known as “fully automatic diaphragm.” The iris diaphragm is fully open before the shot is taken. Shortly before the shutter curtains open, the aperture will close down to the f/number you have set on the aperture ring. Why is this so? A fully automatic diaphragm provides a bright image of the subject that helps you a great deal in focusing the image correctly. But if you use a small aperture, what could appear out of focus in the viewfinder could turn out to be in focus in the picture.

Factors that affect depth of field

Three factors affect the depth of field, namely, the lens opening, the camera to subject distance, and the focal length of your lens.

[1] Changing aperture or lens opening: If you want a wide depth of field, use a small aperture. If you like to have a narrow zone of sharpness, use a big lens opening. Small apertures like f/8, f/11, f/16 or f/22 provide a wide DOF, or enable the camera to render most of your subject sharply and clearly from foreground to back-ground. On the other hand, big or wide apertures like f/1.8, f/2 or f/4 record sharply or clearly only a very shallow or narrow plane. Remember, the DOF is proportional to the lens opening; least at wide apertures, maximum at small apertures.Hyperfocal distance

[2] Changing distance: The closer a subject is to the camera, the shallower the depth of field will be. Or, the closer you are to the subject, the shallower the DOF will be.

[3] Changing the lens: If you want an image with a wide depth of field, then use lenses with short focal lengths like standard or wide angle lenses. If you want a shallow DOF, use lenses like zooms or telephotos.

In talking about maximizing the depth of field, professional photographers often talk about setting the lens to the “hyperfocal distance”. There’s a manual way of setting the lens to its hyperfocal distance, but some people find it a little bit confusing. But if you’re a math nerd, you can simply whip out your calculator and compute the hyperfocal distance according to this formula: H = F2 and then divided by f x 0.033; near limit of DOF = H x u divided by H + (u - F); far limit of the DOF = H x u divided by (H - F), where H is the hyperfocal distance; F= focal length of the lens; f = f/stop; and u = focused distance. Are you happy now?

No comments:

Post a Comment