|

|

A. Introduction

I have a bit of experience in cartooning. In the late 1980s, I collaborated with my former student/editorial cartoonist from Quezon City Science High School in a series of cartoons titled “What’s in a Name?” I conceptualized the cartoons, while my former student drew them. For about two years, the cartoons were published in The Manila Times (it had offices back then in

the Roces Avenue area in Quezon City). If I remember correctly, we were paid around Php 80.00 for every cartoon.

the Roces Avenue area in Quezon City). If I remember correctly, we were paid around Php 80.00 for every cartoon.

I’ve loved cartoons and comic strips since my grade school days. My favorite comic strips were “Mandrake The Magician,” “Phantom,” “Dr. Kildare,” and “Modesty Blaise.” I also liked the Filipino comic strip "Alyas Palos" by the Redondo brothers and the other comics series in the Liwayway magazine.

During my college days, I loved “Hagar The Horrible," which I always looked forward to reading after coming home from church on Sundays. Being a fan of Charles Schulz’s “Peanuts,” I always carried around my copy of the book “The Gospel According to Peanuts"” by Robert Short. In the 1980s, I liked “Calvin and Hobbes,” but the first few times that I read it, I couldn’t understand if Hobbes the tiger was real or not.

The long form comics that I liked was “The Adventures of Tintin.” As I wrote elsewhere, I first read Tintin (“Prisoners of the Sun”) in the garage of my rich neighbor’s house.

During my college days in the late 1970s, I came across the editorial cartoons of Herblock and Oliphant (through my rich neighbor’s copies of magazines such as Time, Newsweek, and The New Yorker).

Sometime in 2005, I was the speaker/judge in photojournalism and editorial cartooning in a Division Press Conference of the Makati City DCS.

B. History and definitions of editorial cartoons and editorial cartooning (with links to ToonMag articles on editorial cartooning); elements of an editorial cartoon; techniques used by editorial cartoonists; the role of an editorial cartoonist; the power of editorial cartoons

From “Political Cartoon” (Wikipedia):

A political cartoon, also known as an editorial cartoon, is a cartoon graphic with caricatures of public figures, expressing the artist’s opinion. An artist who writes and draws such images is known as an editorial cartoonist. They typically combine artistic skill, hyperbole and satire in order to either question authority or draw attention to corruption, political violence and other social ills.

From “Editorial Cartooning” (The Herb Block Foundation):

The first editorial cartoon was drawn by Benjamin Franklin, and appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754 entitled “Join, or Die.” Franklin saw the colonies as dangerously fragmented, and hoped, with the cartoon and an article, to convince colonists they would have great power if they united. Franklin used symbolism and labeling to present an opinion based on current events and politics. Cartoons throughout history have made use of similar techniques of caricature, analogy, irony, juxtaposition and exaggeration to educate and influence their audience.

From “Editorial cartoonist” (Wikipedia):

A strong tradition of editorial cartooning can be found throughout the world, in all political environments, including Cuba, Australia, Malaysia, Pakistan, India, Iran, France, Denmark, Canada and the United States.

From “Brief History of the Editorial Cartoon” (Rochester Institute of Technology):

Editorial and political cartoons derive from satirical art, which may be as old as humanity. Some prehistoric cave art features irreverent human forms (Hess, p. 15); in ancient Egypt an anonymous artist mocked King Tutankhamen’s unpopular father-in-law; later artists criticized Cleopatra (Danjoux 2007); Greek plays and vases anthropomorphized human excess, as in lecherous satyrs; Roman art lampooned behaviors in real or mythical characters like Bacchus, the debauched wine god; in Pompeii, a Roman soldier drew graffiti on his barracks wall mocking a centurion (Hess, p.15); in ancient India, caricatures attacked political elites as well as Hindu gods (Danjoux 2007); Gothic gargoyles decorating medieval churches present caricatures exaggerating human traits.

Whatever the label or medium, satire questions motives, skewers hubris, and invites others to do the same.

In modern journalism, the editor of the Columbia Encyclopedia, Paul Lagasse, defines a cartoon as “a single humorous or satirical drawing, employing distortion for emphasis, often accompanied by a caption.” The editorial – or political – cartoon relies on caricature, stock characters, and cultural symbols to become a “propaganda weapon with social implications” (p.486) — a tool to influence public opinion. The measure of a cartoon’s success is the force of its idea, rendered clearly and resonating beyond its subject of the moment. The artistry is secondary to the message, which should lay bare behavior and character (Press, p.19). In the 18th century, Johnathan Swift wrote advice in a poem to fellow-satirist William Hogarth, “Draw them so that we may trace/All the soul in every face” (Hess, p.16).

From “Cartooning: Political and Editorial”:

Political or editorial cartooning is based on caricatures, a technique dating back to Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. William Hogarth (1697-1764) has been attributed with the early development of political cartoons. In 1732, A Harlot’s Progress, one of his “Modern Morale Series” engravings, was published. His pictures combined social criticism with a strong moralizing element, and targeted the corruption of early 18th century British politics. In the 1750s during a military campaign in Canada, George Townshend (1724-1807), 1st Marquess Townshend produced some of the first overtly political cartoons. He would circulate his ridiculing caricatures of his commander James Wolfe among the troops.

James Gillray (1756-1815), considered the father of political cartooning, directed his satires against Britain’s King George III, depicting him as a exaggerated buffoon, and Napoleon and the French people during the French Revolution. The political climate of Gillray’s time was favorable to the growth of this art form. The party warfare between the Loyalists and Reformists was carried out using party sponsored satirical propaganda prints. Gillray’s incomparable wit, keen sense of farce, and artistic ability made him extremely popular as a cartoonist.

From “Editorial Cartoons: An Introduction” (Ohio State University):

Newspaper editorial cartoons are graphic expressions of their creator’s ideas and opinions. In addition, the editorial cartoon usually, but not always, reflects the publication’s viewpoint.

Editorial cartoons are based on current events. That means that they are produced under restricted time conditions in order to meet publication deadlines (often 5 or 6 per week).

Editorial cartoons, like written editorials, have an educational purpose. They are intended to make readers think about current political issues.

Editorial cartoons must use a visual and verbal vocabulary that is familiar to readers.

From “Art & Politics: 300 Years of Political Cartoons” (First Amendment Museum):

Art has always been intrinsically linked with politics. Nowhere, however, is that link more obvious than in the art of the political cartoon.

Political cartoons convey an artist’s thoughts or opinions on current events, public figures, political questions, and more. The popularity and longevity of political cartoons are a testament to their power as a form of speech.

The biting sarcasm, criticisms, humor, and barbed points found in many political cartoons are often directed at institutions of power, and their creators and publishers rely on First Amendment protections to ensure their legal protection from censorship or government suppression.

Part 1 1720-1800

Part 2: 1800-1850

Part 3: 1850-1900

Part 4: 1900-1950

Part 5: 1950-2000

Part 6: 2000-Present

Elements of an editorial cartoon: (1) caricature and allusion, and (2) context

From “The Evolution of Political Cartoons Through a Changing Media Landscape” by Anne McCallum

To comprehend the origin of the political cartoon, the term must be accurately defined, i.e. what is a political cartoon? According to Dan Backer’s A Brief History of Cartoons website explains how a political cartoon is the melding of two elements. The first element is the caricature and the allusion. The second element is context, i.e. the subject matter is something widely known. In other words the subject matter portrayed by cartoons is something recognizable. The caricature will parody the individual and the allusion will create context. So political cartoons will exaggerate individuals’ features and bring out that individual's “inner self”creating satire. Initially these caricatures and allusions were merely “curiosity” and not “viable artistic productions.” The earliest would be political cartoons were not meant for public viewing (Backer).

Techniques used by editorial cartoonists

From “Editorial Cartooning” (The Herb Block Foundation):

The first editorial cartoon was drawn by Benjamin Franklin, and appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754 entitled "Join, or Die." Franklin saw the colonies as dangerously fragmented, and hoped, with the cartoon and an article, to convince colonists they would have great power if they united. Franklin used symbolism and labeling to present an opinion based on current events and politics. Cartoons throughout history have made use of similar techniques of caricature, analogy, irony, juxtaposition and exaggeration to educate and influence their audience.

From “Analyzing Political Cartoons, Political cartoons: Pictures with a point”:

Cartoonists use several methods, or techniques, to get their point across. Not every cartoon includes all of these techniques, but most political cartoons include at least a few. Some of the techniques cartoonists use the most are symbolism, exaggeration, labeling, analogy, and irony. Once you learn to spot these techniques, you’ll be able to see the cartoonist’s point more clearly.

Symbolism

Cartoonists use simple objects, or symbols, to stand for larger concepts or ideas. After you identify the symbols in a cartoon, think about what the cartoonist intends each symbol to stand for.

Exaggeration

Sometimes cartoonists overdo, or exaggerate, the physical characteristics of people or things in order to make a point.

Labeling

Cartoonists often label objects or people to make it clear exactly what they stand for.

Analogy

An analogy is a comparison between two unlike things that share some characteristics. By comparing a complex issue or situation with a more familiar one, cartoonists can help their readers see it in a different light.

Irony

Irony is the difference between the ways things are and the way things should be, or the way things are expected to be. Cartoonists often use irony to express their opinion on an issue.

The role of the editorial cartoonist

From “Editorial Cartooning, Then and Now” (Medium) by Liza Donnelly citing Ann Telnaes, president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists and a cartoonist for the Washington Post:

“The job of an editorial cartoonist is to expose the hypocrisies and abuses of power by the politicians and powerful institutions in society. I think our role has become even more urgent with the new political reality in 2017. Political dog whistles have become red meat to be tossed out regularly by politicians without the slightest attempt to conceal racism or sexism. Except for journalists and cartoonists, there’s no one keeping a check on conflicts of interest or unethical behavior in government.”

From “The Cartoon” by Herb Block:

“In our line of work, we frequently show our love for our fellow men by kicking big boys who kick underdogs. In opposing corruption, suppression of rights and abuse of government office, the political cartoon has always served as a special prod—a reminder to public servants that they ARE public servants.”

From “Cartoonists - Foot Soldiers of Democracy” (Wikipedia):

“Cartoonists - Foot Soldiers of Democracy” (French: Caricaturistes - Fantassins de la démocratie) is a 2014 documentary film directed by Stéphanie Valloatto about 12 cartoonists around the world who risk their lives to defend democracy. The film premiered in the Special Screenings section at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival. The film was nominated for the César Award for Best Documentary Film at the 40th César Awards.

The documentary features Plantu, French cartoonist, Jeff Danziger, American cartoonist, Rayma Suprani, Venezuelan cartoonist, Angel Boligan, Cuban-Mexican cartoonist, Mikhail Zlatkovsky, Russian cartoonist, Michel Kichka, Belgian-Israeli cartoonist, Baha Boukhari, Palestinian cartoonist, Zoho (Lassane Zohore), Ivorian cartoonist, Damien Glez, Franco-Burkinabé cartoonist, Willis from Tunis (Nadia Khiari), Tunisian cartoonist, Slim (Menouar Merabtene), Algerian cartoonist, and Pi San (Wang Bo), Chinese cartoonist.

The power of editorial cartoons

From “The Power & Perception of Political Caricatures in Light of Recent Cross-Border Controversies by Charlie Hebdo” (Oxford Political Review}:

If a picture is worth a thousand words, it can be said that a satirical cartoon is worth ten thousand. A talented cartoonist can connect with an audience in a way that awakens their imagination when they put pen to paper in the form of caricatures.

Political cartoons are integral to political journalism; employing caricatures and exaggeration to communicate subliminal messages, providing comic relief while making a statement on current affairs. Despite their comedic value, however, political cartoons play a substantial role in political discourse.

Political cartooning is a form of art based on controversy. Caricatures thrive in an environment that promotes debate and freedom of speech; giving them the ability to inform, provoke, and entertain the public. Can political caricatures be too controversial? Who gets to decide? And which side prevails in the inevitable clash between decriers of hate speech and defenders of freedom of expression?

From “The power of the political cartoon” (College Green Group blog):

Immediate, imaginative and frequently impertinent, political cartoons are often far more powerful than the written words which are produced in the space around them. Journalists are often jealous of political cartoonists for this very reason. The cartoonist’s message is clear and understood in seconds, characters are caricatured and delivery is accessible and amusing. An effective cartoon distils information into a single image that resonates with the public perception of an issue or person.

From “Red Lines: Political Cartoons and the Struggle Against Censorship” (The Diplomat):

Cartoons are a powerful tool of political speech. Combining journalism, art, and often satire, political cartoons are all the more powerful because of their accessibility. That also makes them a threat to politicians in democracies and autocracies alike.

Political cartoons are a cross between journalism, art, and satire. At their best, political cartoons combine the public purpose of journalism, the emotive impact of art, and the democratizing effect of satire. Of course, not all political cartoons reach these levels. As with other forms of journalism, many are mediocre. Some are toxic.

From “The power of editorial cartoons” (The Providence Journal):

Editorial cartoons aren’t meant to be fair or balanced, cartoon by cartoon. In getting across one or two key thoughts, with one drawing, how could they be?

For proof, see the accompanying images by Herblock and Oliphant. They’re cartoons we published in the mid-1970s, but they retain their power — and, I’d bet, their power to raise hackles.

If you liked Herblock, Oliphant or Nast back in the day, they were insightful commentators whose work shed light on complex stories. If you disliked them, they were biased, unfair hacks.

From “Editorial Cartoons Pack Powerful Messages” (Voice of America interview with Matt Wuerker of Politico):

“We’re a strange mix of things in that we are making serious commentary on serious topics, but we’re doing it not so seriously,” he says. “We like to see ourselves as opinion columnists that you’d see in a newspaper or somebody on TV who’s offering their opinion… and we get to draw our opinions with silly pictures!”

The Pulitzer-Prize winning cartoonist says the main advantage of a political cartoon is being able to communicate an opinion very quickly.

“I can draw a picture and put in a little word bubble and you can read it in about four seconds and you get it,” he says. “So it’s a very interesting vehicle for expressing an opinion if you do it right.”

“It has to hit you in the face kind of hard and fast and you know it when you’ve been hit.”

The power of editorial cartoons | International Journalism Festival (starts at 1:00 mark)

E. How to analyze or interpret an editorial cartoon

1. The History Skills article first discusses visual codes in political cartoons such as (1) caricature or exaggeration; (2) labelling; (3) symbolism; (4) captions; (5) analogies; and (6) Stereotypes. Afterwards, the article presents these questions to help people in analyzing or interpreting editorial cartoons.

Who or what is represented by the characterisation, stereotypes and symbols?

Who or what have been labelled?

What information is provided by the caption?

What is the political issue being mentioned in the cartoon? (You may need to do some background research to discover this).

What is the analogy that this cartoon is based upon?

Once you have answered these questions, you are ready to answer the final one:

What did the cartoonist want the audience to think about the issue?

2. From Cartoons for the Classroom:

Students determine the meaning of political cartoons through the analysis of their literal, symbolic and figurative meanings of the elements the artist used and their effect. Students are asked to describe the overall effect of the cartoon, and how the artist’s choices combine to create that effect.

Finally, students determine the purpose of the cartoon and how it relates to current issues through discussion questions. A blank cartoon is provided to assist students in writing their own caption based on their understanding of the cartoon’s meaning.

Are books the top danger to kids?

Do political families get big profits?

Is it best of times or worst of times?

Does peace have a chance in Mideast?

How do foes turn into ‘monsters’?

Russia woos its poor neighbor for arms

Why did Elon Musk X-out the bird?

Do history lessons color the future?

Will ignoring global heat destroy us?

Will artificial intelligence replace us?

Is TikTok a threat? Should we ban it?

5 conspiracy-laden cartoons about Taylor Swift

From “10 Things To Look For In Cartoons”:

These are common techniques used by illustrators and are a fantastic starting point in cartoon analysis:

- colour

- size

- labeling

- speech bubbles

- symbols

- focus

- angle

- tone

- facial expression

- context

D. The world’s best editorial cartoonists such as Herblock and Oliphant; Ann Telnaes, one of the most influential editorial cartoonists today

From "Top 10 Greatest Editorial Cartoonists in the History" (ToonsMag):

1. Thomas Nast, 1840s-1880s

Nast (September 26, 1840 – December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the “Father of the American Cartoon.”

2. Herblock (Herbert L. Block, 1920s-2000s)

Herbert Lawrence Block, commonly known as Herblock (October 13, 1909 – October 7, 2001), was an American editorial cartoonist and author best known for his commentaries on national domestic and foreign policy.

During the course of a career stretching into nine decades, he won three Pulitzer Prizes for editorial cartooning (1942, 1954, and 1979), shared a fourth Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for Public Service on Watergate, the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1994), the National Cartoonist Society Editorial Cartoon Award in 1957 and 1960, the Reuben Award in 1956, the Gold Key Award (the National Cartoonists Society Hall of Fame) in 1979, and numerous other honors.

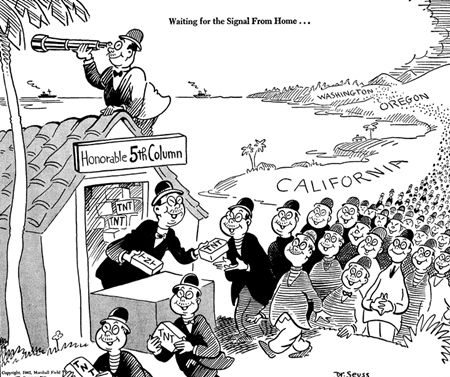

3. Dr. Seuss (Theodore Geisel, 1920s-1990s)

Theodor Seuss Geisel (March 2, 1904 – September 24, 1991) was an American children’s author and cartoonist. He is known for his work writing and illustrating more than 60 books under the pen name Dr. Seuss (/suːs, zuːs/ sooss, zooss). His work includes many of the most popular children’s books of all time, selling over 600 million copies and being translated into more than 20 languages by the time of his death.

From 1941-1943, Geisel, also known as Dr. Seuss, worked as the chief editorial cartoonist for the New York magazine PM, creating over 400 editorial cartoons.

4. Honore Daumier (1800s)

Honoré-Victorin Daumier (February 26, 1808 – February 10, 1879) was a French painter, sculptor, and printmaker, whose many works offer commentary on the social and political life in France, from the Revolution of 1830 to the fall of the second Napoleonic Empire in 1870. He earned a living throughout most of his life producing caricatures and cartoons of political figures and satirizing the behavior of his countrymen in newspapers and periodicals, for which he became well known in his lifetime and is still known today. He was a republican democrat who attacked the bourgeoisie, the church, lawyers and the judiciary, politicians, and the monarchy. He was jailed for several months in 1832 after the publication of Gargantua, a particularly offensive and discourteous depiction of King Louis-Philippe. Daumier was also a serious painter, loosely associated with realism.

5. Bill Mauldin (1920s-2000s)

William Henry Mauldin (October 29, 1921 – January 22, 2003) was an American editorial cartoonist who won two Pulitzer Prizes for his work. He was most famous for his World War II cartoons depicting American soldiers, as represented by the archetypal characters Willie and Joe, two weary and bedraggled infantry troopers who stoically endure the difficulties and dangers of duty in the field. His cartoons were popular with soldiers throughout Europe, and with civilians in the United States as well. However, his second Pulitzer Prize was for a cartoon published in 1958, and possibly his best-known cartoon was after the Kennedy assassination.

6. Pat Oliphant (1960s-2015)

Patrick Bruce “Pat” Oliphant (born 24 July 1935) is an Australian-born American artist whose career spanned more than sixty years. His body of work as a whole focuses mostly on American and global politics, culture, and corruption; he is particularly known for his caricatures of American presidents and other powerful leaders. Over the course of his long career, Oliphant produced thousands of daily editorial cartoons, dozens of bronze sculptures, as well as a large oeuvre of drawings and paintings. He retired in 2015.

Patrick Bruce “Pat” Oliphant (born 24 July 1935) is an Australian-born American artist whose career spanned more than sixty years. His body of work as a whole focuses mostly on American and global politics, culture, and corruption; he is particularly known for his caricatures of American presidents and other powerful leaders. Over the course of his long career, Oliphant produced thousands of daily editorial cartoons, dozens of bronze sculptures, as well as a large oeuvre of drawings and paintings. He retired in 2015.

From “Pat Oliphant” (Illustration History):

Not one to shy away from controversy, Oliphant intentionally submitted a work he felt was inferior to the Pulitzer Prize board. When it won, he criticized the board for selecting his cartoon for its subject matter (Ho Chi Minh carrying the body of a dead Vietnamese man in the posture of the Pietà) rather than the quality of the work. After that, he was a regular critic of the Pulitzer and refused to be considered for the award again.

7. David Low (1920s-1950s)

Sir David Alexander Cecil Low (7 April 1891 – 19 September 1963) was a New Zealand political cartoonist and caricaturist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom for many years. Low was a self-taught cartoonist. Born in New Zealand, he worked in his native country before migrating to Sydney in 1911, and ultimately to London (1919), where he made his career and earned fame for his Colonel Blimp depictions and his satirising of the personalities and policies of German dictator Adolf Hitler, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and other leaders of his times.

8. Ralph Steadman (1960s-present)

Ralph Idris Steadman (born 15 May 1936) is a British illustrator best known for his collaboration with the American writer Hunter S. Thompson. Steadman is renowned for his political and social caricatures, cartoons and picture books.

9. Charles Addams (1930s-1980s)

Charles Samuel Addams (January 7, 1912 – September 29, 1988) was an American cartoonist known for his darkly humorous and macabre characters. Some of his recurring characters became known as the Addams Family, and were subsequently popularized through various adaptations.

Addams drew more than 1,300 cartoons over the course of his life. Beyond The New Yorker pages, his cartoons appeared in Collier’s and TV Guide,[5] as well as books, calendars, and other merchandise.

10. Jules Feiffer (1950s-present)

Jules Ralph Feiffer (born January 26, 1929) is an American cartoonist and author, who at one time was considered the most widely read satirist in the country. He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for editorial cartooning, and in 2004 he was inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame. He wrote the animated short Munro, which won an Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film in 1961. The Library of Congress has recognized his “remarkable legacy”, from 1946 to the present, as a cartoonist, playwright, screenwriter, adult and children’s book author, illustrator, and art instructor.

Ann Telnaes, one of the most influential editorial cartoonists today

| Ann Telnaes’s cartoon gifs start on pen and paper Ann Telnaes on political memes, GIFs and traditional cartooning Ann Telnaes – Women in Cartooning Ann Telnaes - The Influence Of The Cartoonist |

In 2001, Telnaes became the second female cartoonist and one of the few freelancers to win the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning. In 2017, she received the Reuben Award (National Cartoonists Society) and thus became the first woman to have received both the Reuben Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning.

From The Washington Post:

Ann Telnaes creates editorial cartoons in various mediums — animation, visual essays, live sketches and traditional print — for The Washington Post. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 2001 for her print cartoons, the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year for 2016 and the Herblock Prize for editorial cartooning in 2023. In 2022, she was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for her illustrated reporting and cartooning. Telnaes’s print work was shown in a solo exhibition at the Great Hall in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress in 2004.

Other awards include the National Cartoonists Society Reuben division award for Editorial Cartoons (2016), the National Press Foundation’s Berryman Award (2006), the Maggie Award, Planned Parenthood (2002), 15th Annual International Dutch Cartoon Festival (2007), the National Headliner Award (1997), the Population Institute XVII Global Media Awards (1996), and the Sixth Annual Environmental Media Awards (1996). Telnaes is a past president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists and is a member of the National Cartoonists Society.

From “Humor’s Edge: Cartoons by Ann Telnaes” (Library of Congress):

In 2001 Ann Telnaes became the second woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning, a highly competitive field in which fewer than 5 percent of the practitioners are women. During the eighty-one years the award has been given, all but a few winners have been affiliated with a newspaper. As a freelancer and a woman cartoonist, Telnaes is thus doubly unusual among Pulitzer winners. The Pulitzer Prize committee awarded her the prize for “a distinguished cartoon or portfolio of cartoons published during the year, characterized by originality, editorial effectiveness, quality of drawing, and pictorial effect.” Her drawings exemplify these qualities in dynamic, inventive compositions, which capture humorous and dismaying aspects of the election, communicate the candidates’ foibles and flaws, and convey her unflinching views on the roles of the Florida legislature and U.S. Supreme Court in the election’s outcome.

In Ann Telnaes’s Washington Post columns, you can see her best editorial cartoons of 2019, 2021, and 2022.

E. Pultizer Prize — the world’s most prestigious award in journalism: Editorial Cartooning winners from 1922 to 2023

The Pulitzer Prize is an award administered by Columbia University for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition in the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fortune as a newspaper publisher.

As of 2023, prizes are awarded annually in 23 categories. In 22 of the categories, each winner receives a certificate and a US$15,000 cash award, raised from $10,000 in 2017. The winner in the public service category is awarded a gold medal.

As of 2023, prizes are awarded annually in 23 categories. In 22 of the categories, each winner receives a certificate and a US$15,000 cash award, raised from $10,000 in 2017. The winner in the public service category is awarded a gold medal.

In 2022, the Editorial Cartooning prize was superseded by the revamped category of Illustrated Reporting and Commentary. In response, the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists “issued a statement calling for the Pulitzer board to reinstate Editorial Cartooning as its own category while also recognizing Illustrated Reporting as a separate form.”

Here’s how to navigate the Editorial Cartooning section of the website:

1. Click the “+” symbol opposite, for example, the year 2020.

2. The drop down list will show the following as the winner and finalists:

Barry Blitt, contributor, The New Yorker

For work that skewers the personalities and policies emanating from the Trump White House with deceptively sweet watercolor style and seemingly gentle caricatures.

Kevin Kallaugher, freelancer

Lalo Alcaraz, freelancer

Matt Bors of The Nib

3. If you click “Barry Blitt, contributor, The New Yorker,” for example, this will lead you to the page where the series of the winning editorial cartoons are posted.

The Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning has been awarded twice to comic strip artists, the first being Garry Trudeau in 1975 for his “Doonesbury” comic strips.

Examples of editorial cartoons by Matt Weurker of POLITICO (2012 Pulitzer Prize winner):

|

| Click the GIF above to view a bigger copy in another tab. |

F. Sources and examples of excellent editorial cartoons (Washington Post; U.S. News & World Report; The List Wire; The Week; Cartoon Movement)

Editorial Cartoons, Washington Post

Cartoons (The Week)

U.S. News & World Report Cartoons: Immigration; Joe Biden; Republican Party; 2024 Election; Gun Control and Gun Rights; Congress; Donald Trump; Climate Change; Middle East; Education; Ukraine and Russia; Politics, current events and international news

The List Wire (part of the USA Today Sports Network):

The greatest political cartoons in recent history

The best political cartoons in recent history

Year in Review: The best political and editorial cartoons of 2023

Greatest holiday-themed political cartoons in recent history

The best editorial cartoons of 2022

Cartoon Movement:

“A global platform for editorial cartoons and comics journalism, Cartoon Movement is an online platform bringing together professional editorial cartoonists from all over the world, offering daily perspectives on what is happening in the world.”

“With a community of over 500 cartoonists in more than 80 countries, we bring you the best political cartoons every day. Our mission is to promote professional editorial cartooning and to defend freedom of speech.”

Most recent

Relevance

G. Animation and graphic novels: the future of editorial cartoons?

Examples of Rappler editorials (in Taglish) with animated editorial cartoons

Cha-Cha-pwera! SMNI, karma daw ang tawag diyan Justice, Philippine style: Acquitted sa plunder, pero may kabig naman |

Animated political cartoons are the evolution of the editorial cartoon. The animated political cartoons are normally written in Flash.

With the dot com crash at the turn of the millennium, artists and animators were among the first to be let go at online news sites. Early pioneers such as Pat Oliphant stopped adding content shortly after. Others, however, have carved out a market for their trade. JibJab is the most notable, making Internet history with their cartoon This Land! in 2004. Mark Fiore’s animations have appeared in SFGate for years, he appears to be the most successful animator, currently publishing his cartoons once a week. Zina Saunders creates regular animations for Mother Jones.

Innovative new cartoonists, such as J83 (independent), and Shujaat Ali from the Aljazeera news website, are also appearing and making inroads in this evolving medium. Australian 3d animated political cartoonist inspired by the team at India Today that produce the award winning ’So Sorry’ animated political cartoons, TwoEyeHead has been one of the world’s few dedicated and regular 3D animated political cartoonists since 2014. Used by many Australian news services the looping 3D cartoons, specifically developed for social media, have been viewed by millions and can be found at @twoeyehead on Twitter. Peter Nicholson, of The Australian newspaper, publishes a new animation fortnightly, featuring the voices of mimic Paul Jennings. In Britain, Matthew Buck (Hack) launched the first regular animated political cartoon for Tribune magazine in May 2007 and subsequently started to work, weekly, for Channel 4 (News website). After the Channel 4 work ceased with the financial problems at ITN, his work - The Opinions of Tobias Grubbe - reappeared at the Guardian during the UK General Election of 2010.

From “The animated moving image as political cartoon” by Lucien Leon (lecturer in Animation and Video at the Australian National University’s School of Art and Design in Canberra)

For all the technological developments that have punctuated the timeline of political cartooning, the digital media revolution has ushered in an era where cartoonists find themselves, for the first time, operating in a news-publishing context that supports both silent static images and audio-visual moving images . Animation has emerged as a vehicle that exploits both the cartoonist’s customary drawing skills as well as the new-media affordances of sound and motion. Categorically acknowledged by some prize-giving institutions but not others, and accepted by some (but not all) cartoonists, the place of animation in the political cartooning tradition remains nebulous. In this article I examine and compare the material and teleological characteristics of print media political cartoons and animated political cartoons. Writing primarily from an Australian perspective, I take as my set selected works of five prominent Australian political cartoonists who have also negotiated an animation practice. I conclude that political animations diverge from printmedia political cartoons in terms of visual style, but not function. In critically reflecting on the viewpoints of prize givers, scholars and cartoonists themselves, I determine that the alignment of the two image types within a single, political cartooning tradition is not only possible in a categorical sense, but also desirable in a historical sense.

Graphic novel as editorial cartoon

In 2018, the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning was awarded to Jake Halpern, freelance writer, and Michael Sloan, freelance cartoonist, The New York Times “for an emotionally powerful series, told in graphic narrative form, that chronicled the daily struggles of a real-life family of refugees and its fear of deportation.”

H. Editorial cartooning in the Philippines: history and origins; personalities and publications

1. “Comic Art in the Philippines” by John A. Lent, Philippine Studies, vol. 46, no. 2 (1998): 236–248, Ateneo de Manila University

Editorial cartooning in the Philippines dates at least to the end of the nineteenth century. National hero Jose Rizal, credited with drawing the first cartoon, ’The Monkey and the Tortoise" (1886), used caricature in his propaganda against the Spaniards (Marcelo 1980,18), as did satirical magazines, such as Te con leche, El tio verdades, Biro-Biro, and Miau, which appeared between 1898 and 1901, designed mainly to lampoon both Spaniards and Americans (Esteban 1953,7-8). The anonymously edited, weekly Miau, named after a worldly cat which knew everything, consisted of fifty percent cartoons.

Maurice Jimena, the speaker in the Explained.ph video on editorial cartooning gives an overview (from 32:00 mark up to around 47:50) of Lent’s paper as to personalities and publications such as Liwayway and Philippines Free Press, published in 1908.

Maurice Jimena, the speaker in the Explained.ph video on editorial cartooning gives an overview (from 32:00 mark up to around 47:50) of Lent’s paper as to personalities and publications such as Liwayway and Philippines Free Press, published in 1908.

From Wikipedia: Juan dela Cruz, the male national personification of the Philippines and counterpart to Maria dela Cruz, first appeared in the Philippines Free Press in 1946.

2. “Philippine Cartoons: Political Caricature of the American Era 1900-1940” (1900-1941) by Alfred W. McCoy and Alfredo Roces

2. “Philippine Cartoons: Political Caricature of the American Era 1900-1940” (1900-1941) by Alfred W. McCoy and Alfredo Roces

McCoy and Roces “compiled 377 political cartoons from the American era in the Philippines (1900-1941) that satirized society, politics, and the transition from Spanish to American rule. The cartoons provide insight into how Filipinos viewed the changes brought by the Americans and the turbulent times.”

I. The demise of editorial cartoons in the USA?; The Philippine Daily Inquirer and the Philippine Star stopped publishing editorial cartoons as of 2022

The demise of editorial cartoons in the USA?

| As early as 2004, organizations and people (including editorial cartoonists) have warned of the impending demise of editorial cartoons.

From “The Fixable Decline of Editorial Cartooning” (Nieman Reports, 2004): The sad state of editorial cartooning is a result of the current economics of the newspaper industry and of editors who have little appreciation for political satire. As the newspaper industry has declined in both readership and influence so, too, has journalistic decision-making by editors, many of whom opt for publishing generic syndicated cartoons over provocative, staff-drawn cartoons. They do this because the cartoons are cheaper, and they generate fewer phone calls and e-mails from readers. Too many editors want editorial cartoons to be objective, like news stories. But that’s not what editorial cartoons are supposed to do. Cartoonists are right to blame editors and publishers for not taking their art seriously. But why should editors do this when cartoonists don’t take themselves seriously? Too much of editorial cartooning today is instantly forgettable. Too many cartoonists rely on their first drafts, which explains why so many cartoons are superficial or look like one another. They’ve abandoned the sense of righteous indignation that inspires the profession’s best instincts, or its “killer angels,” as Marlette put it. Marlette was once asked what makes a good cartoon, and he answered, “Can you remember it? Did it tattoo your soul?” From “Editorial cartoons: Is the end nigh?” by Jake Fuller, editorial cartoonist (February 2005): Granted, the job market for my craft has been steadily shrinking. Twenty years ago, there were editorial cartoonists on staff at close to 200 newspapers. Today, there are fewer than 90. And the reasons for this tragic and foolish turn of events have been hashed over ad nauseam. The reasons include: the evil corporate culture that has descended upon the newspaper business during the past two decades, sucking profits away from local papers; circulation is down; budgets are tight and newsprint costs are soaring. So, the guy who just sits around drawing pictures and infuriating readers has “expendable employee” written all over him. OK, those are all legitimate reasons completely out of the control of our ink-stained hands. But apparently, cartoonists have aided in bringing on their current plight. Call it the “syndication mindset.” [Boldfacing supplied] |

The last few years have seen many troubling developments that all point in just one direction: the demise of political cartooning. A short recap:

- In 2019 the (international edition of the) New York Times decided to stop running political cartoons.

- In 2021, no Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartoons was given.

- In 2022, the Pulitzer Prize decided to change the name of the category Editorial cartoons to Illustrated Reporting and Commentary.

- Also in 2022, Gannett , a large US newspaper company with 250 titles decided that the time for a traditional editorial page (the home of the political cartoon) has come and gone.

2. From “A Scary and Shortsighted Decision”: New York Times to Stop Publishing Political Cartoons (June 11, 2019)

After the cartoon controversy in April, when the international edition of the New York Times ran a cartoon featuring Trump and Netanyahu that was widely criticized as being antisemitic, the NY Times decided to stop running cartoons from the CartoonArts International syndicate.

Now, they have decided to stop running political cartoons altogether, ending contracts with their two regular cartoonists, Heng and Chappatte.

3. From “The end of political cartoons at The New York Times” (June 10, 2019)

All my professional life, I have been driven by the conviction that the unique freedom of political cartooning entails a great sense of responsibility.

In 20-plus years of delivering a twice-weekly cartoon for the International Herald Tribune first, and then The New York Times, and after receiving three Overseas Press Club of America awards in that category, I thought the case for political cartoons had been made (in a newspaper that was notoriously reluctant to the form in past history.) But something happened. In April 2019, a Netanyahu caricature from syndication reprinted in the international editions triggered widespread outrage, a Times apology and the termination of syndicated cartoons. Last week, my employers told me they’ll be ending in-house political cartoons as well by July. I’m putting down my pen, with a sigh: that’s a lot of years of work undone by a single cartoon - not even mine - that should never have run in the best newspaper of the world.

I’m afraid this is not just about cartoons, but about journalism and opinion in general. We are in a world where moralistic mobs gather on social media and rise like a storm, falling upon newsrooms in an overwhelming blow. This requires immediate counter-measures by publishers, leaving no room for ponderation or meaningful discussions. Twitter is a place for furor, not debate. The most outraged voices tend to define the conversation, and the angry crowd follows in.

4. From “Gannett Slashes Editorial Pages from Papers — Along with Cartoons” by JP Trostle (2022):

Word has trickled down from Gannett (née GatehouseMedia) that, beginning June 1, they will be stripping out the daily editorial/opinion section in the print editions of all their daily papers. Gannett, the largest newspaper publisher in the country as measured by total daily circulation, announced their Op/Ed pages will now only appear in print on Wednesdays and Sundays. (If that— one cartoonist who freelances at a Gannett-owned paper said their editor told them it would only be Sunday.)

While some editors at the affected newspapers spun this as a good and necessary move, noting that local editorials and letters to the editor could still be found online, Mary Kelli Palka at the Florida Times-Union flatly wrote that content was being slashed: “We also no longer have access to syndicated content, though we had stopped running many syndicated columns years ago. But it does mean we’re losing syndicated cartoons. This has all made us rethink our editorial pages.”

Cartoonists were swift to respond. “Bad news for editorial cartoonists for sure, as well as really horrible news for an informed citizenry in the communities these papers are supposed to serve,” wrote Jimmy Margulies, the award-winning political cartoonist who spent more than two decades on the staff of The Record in northern New Jersey, one of the papers hit by the cuts.

Some cartoonists, posting on a private message board for AAEC members, said their freelance work in Gannett-owned papers would be affected.

5. From “No More Editorial Cartoons?” by Daryl Cagle:

Newspaper editorial cartoons are disappearing when they are most needed.

My own cartoons often used to appear in my local Los Angeles Daily News – not anymore. The Daily News and about a dozen associated, conservative-leaning papers surrounding Los Angeles, eliminated their traditional, daily spot for an editorial cartoon, running only one cartoon in their Sunday editions; these papers now have no editorial page at all on Mondays and Saturdays. Many small newspapers are dropping their editorial pages entirely. Some editors tell me that editorial pages “only make readers angry” and “don’t bring in advertising income.”

The Los Angeles area is now an editorial cartoon desert. The Los Angeles Times, a newspaper with a rich editorial cartooning history, runs only one cartoon per week, on low-circulation Fridays.

A mid-sized, conservative, Pennsylvania newspaper, The Butler Eagle, recently created some buzz in the cartooning community by leaving their regular cartoon spot blank as a protest, because the editor couldn’t find a cartoon that he liked.

We read a lot about editorial cartoonists and other journalists losing staff jobs, but we don’t read much about newspapers dropping editorial cartoons. This plague is accelerating as conservative, timid or budget-strapped newspaper editors are becoming more vocal in pushing back against cartoons.

6. From “Editorial cartoonists’ firings point to steady decline of opinion pages in newspapers” (AP News):

Even during a year of sobering economic news for media companies, the layoffs of three Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonists on a single day hit like a gut punch.

The firings of the cartoonists employed by the McClatchy newspaper chain last week were a stark reminder of how an influential art form is dying, part of a general trend away from opinion content in the struggling print industry.

At the start of the 20th century, there were about 2,000 editorial cartoonists employed at newspapers, according to a report by the Herbert Block Foundation. Now, Ohman estimates there are fewer than 20.

7. From “Newspaper Apologizes for Editorial Cartoon, Bans Cartoonist from Their Pages“ (June 2023):

On Wednesday The Quad City Times published a cartoon by Leo Kelly taking a swipe at MAGA racism, but the cartoon invoked a Simpsons character whose name has become offensive to many and so the tables were turned with the newspaper and the cartoonist being accused of racism.

As is customary the cartoonist is punished, the approving editor gets a pass.

8. From “The New York Times cuts all political cartoons, and cartoonists are not happy”:

The New York Times is again making news for how it handles editorial cartoons — or in the latest turn, will not handle editorial cartoons.

Beginning next month, the Times will cease running daily political cartoons in its international edition, editorial page editor James Bennet said Monday in a statement — a move that brings the overseas newspaper “into line with the domestic paper,” which in recent years had ceased running weekly roundups of syndicated cartoons and experimented instead with longer-form editorial comics.

9. From “Op-ed: Is this the end of editorial cartooning?”:

The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists will have its (online) annual convention this weekend where cartoonists, or at least the few who are still working, will be reminded of what they already knew: Editorial cartooning is a dying profession.

The AAEC conventions used to be raucous and important affairs, including speeches by presidents and other influential politicians. Nowadays, they’re like reunions of World War II veterans; each year fewer return, and those who do wax nostalgically about the good old days when they protected America from those who wanted to do it harm.

Today, there are fewer than 40 full-time cartoonists, fewer than at any time since newspaper editors began hiring cartoonists in the late 19th century. Four months ago, the Pulitzer Prize failed to name a winner in the category of editorial cartooning for the first time in nearly a half century.

It’s too early to write an obituary for editorial cartooning. It is not too late to write an appreciation.

10. From “The New York Times’ decision to cut cartoons is a sad moment for journalism” (The Week):

With the annihilation of its editorial cartoon section, the paper gives up one of journalism’s — and democracy’s — greatest weapons.

Although Bennet claimed the paper had been mulling eliminating the section for "well over a year," the timing seems suspicious to some. In April, the Times had published a cartoon of President Trump walking Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu like a dog; in its apology, the Times rightfully identified the illustration as "clearly anti-Semitic and indefensible." The paper then sweepingly "suspended the future publication of [all] syndicated cartoons," from which the offending image had been pulled; then, only two months later, Bennet announced the paper’s last vestige of commitment to editorial cartoons was being erased, too.

The Philippine Daily Inquirer and the Philippine Star stopped publishing editorial cartoons as of 2022

1. From “Editorial cartoons and the long journey of political commentary” (Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility) September 3, 2022:

The slide of print as a source of news continues. And the decision to cut out cartoons from more Op-Ed pages is poignant.

Last August 30, on National Press Freedom Day, Cartoonist Zach announced in his Facebook page the “heartbreaking news” that another national newspaper, The Philippine Star, will no longer be publishing editorial cartoons. He recalled that last March, the Philippine Daily Inquirer ceased publishing the same. The Foundation for Media Alternatives released an editorial cartoon in their Facebook page by Tarantadong Kalbo, another cartoonist enjoying a wide following. A pen and an ink bottle, both drawn as animated objects, were walking out of the pages of the top two dailies.

Reviewing the two newspapers’ recent issues, CMFR found that the Star last published an editorial cartoon on August 9, while Inquirer’s last cartoon was on February 28, 2022. Both publications were repeatedly included in CMFR’s “Editorial Cartoons of the Week” page due to their cartoons’ sharp and effective messaging.

2. From “Press cartoons in the Philippines: between vitality and scarcity” (Cartooning for Peace):

These are sad news that probably mark the end of an era, as the Center For Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) points out in a comprehensive article published in reaction to Zach’s tweet. The organisation points out, however, that the end of publication in these newspapers is balanced by the rise of a generation of cartoonists active on social networks, including “Zach, Tarantadong Kalbo, Kapitan Tambay, and Isang Tasang Kape.”

3. From “Artists tackle challenges, threats faced in editorial cartooning” (Rappler, May 10, 2023):

Cartoonists Zach and StephB, from the artist collective Pitik Bulag, share some of the challenges and problems they face as editorial cartoonists in the country and how they manage to keep the art alive.

Being a political cartoonist in the Philippines (interview with Cartoonist Zach)

Cartoons have been a powerful way to convey a stand on issues and a call to action. But in today’s digital age, cartoonists are facing a pressing problem.

In an interview with Rappler, cartoonists Zach and StephB, described the murky situation of editorial cartooning in the Philippines.

For one, editorial cartoons were removed in at least two major print publications in 2022. First, The Philippine Daily Inquirer scrapped editorial cartoons in March. This was followed by The Philippine Star, which also ended the inclusion of editorial cartoons in its op-ed pages in August.

J. Miscellaneous resources on the making of an editorial cartoon and the art of caricature

1. Michael Edward Luckovich (born January 28, 1960) is an editorial cartoonist who has worked for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution since 1989. He is the 2005 winner of the Reuben, the National Cartoonists Society’s top award for cartoonist of the year, and is the recipient of two Pulitzer Prizes.

2. Kal: the making of a political cartoon (editorial cartoonist for The Economist magazine)

3. Patrick Chappatte: The Making Of an Editorial Cartoon

4. Joe Heller and His Work as an Editorial Cartoonist (USA Today, New York Times, The Compass News): elements of an editorial cartoon

5. Funny Business - An Inside Look at the Art of Cartooning

6. Toca Mocha

7. How To Draw A Caricature Using Easy Basic Shapes

8. The Caricature Drawing Exercise That Changed My Life: Six Steps to Awesomeness

9. Tom Richmond (born May 4, 1966) is an American freelance humorous illustrator, cartoonist and caricaturist whose work has appeared in many national and international publications since 1990. He was chosen as the 2011 “Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year”, also known as “The Reuben Award”, winner by the National Cartoonists Society.

9. Tom Richmond (born May 4, 1966) is an American freelance humorous illustrator, cartoonist and caricaturist whose work has appeared in many national and international publications since 1990. He was chosen as the 2011 “Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year”, also known as “The Reuben Award”, winner by the National Cartoonists Society.

Now a major contributor to Mad, Richmond’s caricatures and cartoons illustrate many of Mad’s trademark movie and TV parodies. He was the first illustrator in the modern (non-comic book) era to do his TV and film parodies in full color, coinciding with Mad’s switch to a color format in 2001. In addition to MAD, Richmond continues to do freelance illustration for a variety of publications and advertising clients.