|

| Free e-book: Creative lens techniques How to shoot images with impact (21 pages; 7.28 MB) |

I remember one student in the 1980’s who quite innocently asked me, “Sir, does your camera have a lens?” Well, all cameras, whether digital or film-based, have lenses, except of course, when we’re talking about the pinhole camera (the “camera obscura” of ancient history). A lens is a transparent, optical device made up of glass or high tech plastic, and is capable of “refracting” or bending light.

Most of you, at this point in time, are probably using digital cameras. Your camera thus comes with a built-in lens that allows you to shoot groups or close-ups at the touch of a button. For those of you who are joining the photojournalism competitions in the various levels of the press conferences, you are still bound by the contest rules to use film-based cameras. For the grade school level of competitions, students are allowed to use 35 mm compact, point and shoot cameras. For the high school level, however, the participants are required to use single lens reflex cameras. As we discussed before in “I Am A Camera,” SLR cameras (unlike compact, point and shoot cameras) are distinguished by an interchangeable system of lenses.

Focal length of a lens

One of the most important considerations in buying or using a lens is its focal length, which is the distance, measured in millimeters, between the optical center of the lens and the film plane when the lens is focused at infinity.

The focal length of a lens determines two things:

(1) the magnification of the image (how big or how small the image appears), and

(2) the field of view (how much of the scene will appear in the photograph).

Don’t fall into the fallacy, however, that the longer the lens, the better your photographs will be. I remember during the 50th anniversary of the National Secondary Schools Press Conference in 1993 held in Rizal High School in Pasig, a lot of the photojournalism participants were in awe with one NCR delegate whose camera had a long, long, long, long lens. They kept saying that this delegate was definitely going to win the contest. Well, he didn’t win any place at all.

Henri Cartiér Brésson is a revered name among photographers. His goal of capturing the “decisive moment” probably best sums up what photojournalism is all about. And by deliberate choice, what kind of lens did he use? What else but the 50 mm lens or the so called standard or normal lens, which is the lens you most probably have on your single lens reflex camera right now, right? Right!

Take note of the minimum focusing distance of your lens

A note of caution. All lenses (whether for digital or film-based cameras) have their “minimum focusing distance,” which is the limit as to how close a lens can focus. This is determined by the lens design and by how far the lens can be extended by its focusing ring. With 35 mm compacts (allowed in the grade school level press conferences), the lens generally is pre-set to render in focus subjects which are around 5 feet away from the camera up to infinity. If you try to shoot something which is below the minimum focusing distance, that subject will be out of focus.

Wikipedia has excellent, easy to understand articles on the different kinds of lenses, and on apertures and lens openings. Please browse these articles before proceeding with this lesson on lenses, okay?

Versatility of a zoom lens

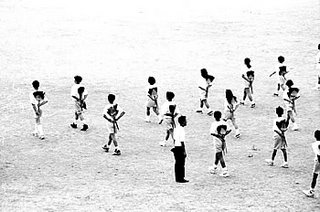

I shot the following pictures using my beloved Canon AE-1 Program camera and my Vivitar f/3.5~5.6, 28-210 mm zoom lens. A zoom lens is two or three lenses rolled into one. With this zoom lens, I was able to shoot wide angle shots of groups, and telephoto (meaning, magnified) shots of faraway subjects.

With the pictures above, I used the 28 mm (wide angle) end of my zoom lens. Without having to move back, I was able to include almost the whole athletic oval where hundreds of students were performing for the Field Demonstration. Now take a look at the next picture.

I then zoomed in on the students at the center of the athletic oval, using the 210 mm (telephoto end) of my zoom lens. I didn’t move from the position I was in when I took the 2nd wide angle shot above, but my zoom lens allowed me to shoot a close-up of the group of students performing in the middle of the oval.

I then zoomed in on the students at the center of the athletic oval, using the 210 mm (telephoto end) of my zoom lens. I didn’t move from the position I was in when I took the 2nd wide angle shot above, but my zoom lens allowed me to shoot a close-up of the group of students performing in the middle of the oval.The pictures below illustrate the versatility of a zoom lens, that is, from wide angle shots, I was able to shoot close-ups of my subjects.

Telephoto lenses compress linear perspective

(Note: To be technically accurate about it, it is not the focal length of the lens but the camera-to-subject distance that produces the compressed or stacked perspective.)

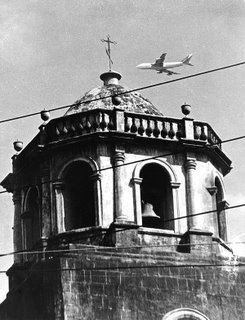

Telephoto lenses appear to compress linear perspective, that is, background details seem to move toward you, and objects that in reality are far apart look or appear much closer than they really are. If you watch any sports event, for example, on television, the spectators in the background look deceivingly much closer to the players in the foreground. This effect is known as “stacked perspective”, “compressed” perspective or “squashed” perspective.

Take the picture above of the marching cadets, for example. We all know how wide a platoon is, with nine cadets (or elements) in each squad. Notice, however, that the cadets seem so close to each other, like they were squashed together in a single shallow plane. Like I said, this effect is known as “compressed perspective” among other names. (Pssst, guys, check your alignment!)

The picture above is another example of compressed perspective. An airplane seems just about to crash towards the church tower. (Memories of 911!) The plane and tower are really far apart, but the telephoto end of my zoom lens produced this compressed perspective.

Wide angle lenses, distortion, and the keystoning effect

When you want a great depth of field, that is, everything in the picture must be recorded sharply, from foreground to deep background, you have to use a wide angle lens. Pictures shot with a wide angle lens have a strong sense of depth and distance.

On the other hand, the most significant disadvantage of wide angle lenses is distortion. If there are circular objects at the corners of the frame, they become distorted, taking on oval shapes. If you’re shooting crowd scenes for example, heads of persons near the frame corners will become distorted. Wide angle lenses are thus not suited for close up portraits.

Also, if you tilt the camera even a little upward, parallel vertical lines of the subject (like those of the building above) will converge towards the top or bottom of the picture. This is the so-called “keystoning” effect.

Trivia on lenses

1. Bill Foley won the 1983 Pulitzer Prize, the most prestigious prize in journalism, for his photo coverage of the Sabra and Shattila massacres in Lebanon where Christian militiamen murdered Palestinian civilians in these two refugee camps.

One time, Foley and Time photographer Bill Pierce were picked up at a checkpoint manned by Syrian soldiers who suspected them of being spies for the Israeli army which had invaded Lebanon. They were detained and beaten up.

Foley had a handheld light meter which naturally had the various f-numbers/apertures indicated on its exterior. One of the Syrian soldiers manning the checkpoint was convinced that the “f/16” marking on Foley’s meter was a means for communicating with Israeli F-16 fighter jets!

2. Distortions and converging lines created by wide angle lenses are generally treated as liabilities but as you master the basics of photography, you will learn to use these liabilities creatively in order to come up with better pictures.

3. So you’re stuck with your dinky standard lens, with no money to buy those monster zoom or telephoto lenses you see professional photographers carry around ... You wonder how in the world you can ever improve your skills without those long lenses. Well, what lens did Hénri Cartiér Brésson or Eduard Masferré (a Belgian photographer whose pictures of the Ifugaos and other mountain tribesmen may be considered as national treasures) use? What else but the very same dinky standard lens you have!

4. “Perfect Strangers” was a very popular television sitcom in the 1980’s and early 1990’s. The show told the stories of Balki, an innocent, naive immigrant to the US and his cousin Larry, a struggling photojournalist who never seemed to run out of troubles primarily because of his insecurities, get rich quick schemes and his bloated ego.

But Balki would always come to Larry’s rescue, and Larry would always see the error of his ways. While we felt good about Balki’s innocence, we also readily identified with Larry’s insecurities, his foibles and his failures.

In one episode, Balki and Larry went to a photo exhibit by a renowned photographer. Larry wanted to meet the photographer whom he thought could help him in his career as a photojournalist but the highbrow hosts of the exhibit didn’t give him the chance.

Depressed, Larry began criticizing the photographs, especially that of a solitary man along a highway. Larry said that the photographer should have used a 24 mm wide angle lens instead of a 28 mm lens. Or was it a 20 mm lens instead of a 24 mm? Anyway, the host of the exhibit who overheard these remarks promptly and publicly scolded Larry for daring to criticize the photograph.

While Larry was stammering his way towards an explanation, the world famous photographer asked him why a 24 mm lens should have been used. Larry answered, quite correctly as the photographer would later on say, that a 24 mm lens would dramatically “increase the photograph’s sense of isolation.”

Just for once, Larry was right, and we all felt, I’m sure, really, really good about Larry’s vindication.